The childhood and youth of Siddhartha, the future Buddha of our cosmic cycle, take place in a privileged and very protected environment. He is the firstborn, his father intends to make him his successor and it is out of the question that the young prince, possibly inspired by some painful event, chooses the path of renunciation envisaged by the sages shortly after his birth. But things seem to be in line with the king's wishes, the prince now has a wife, after several years of marriage, the birth of a child is on the horizon and he will not be able to shirk his family responsibilities, then his duty. of heir to the throne.

However, as he approaches his thirtieth birthday, he wonders, because everything does not seem as perfect to him as they try to make him believe and comes to him the desire to discover the world beyond the confined limits of his residence. .

The shock of reality

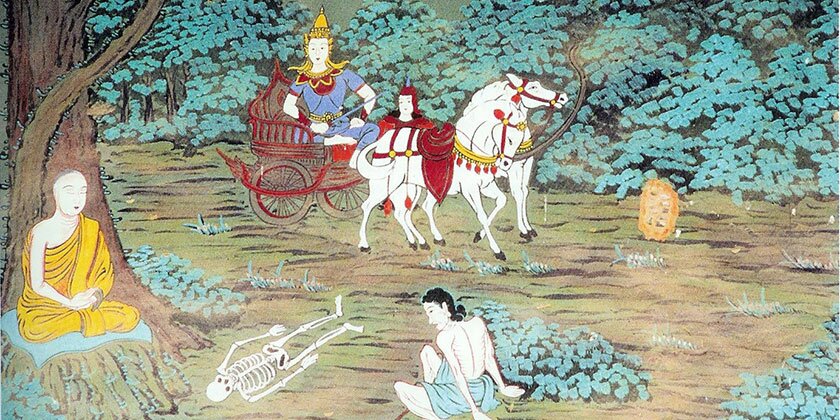

He summons his squire and has his chariot brought to visit the city. Some texts report that his father, informed of his intentions, had the streets cleaned and decorated and ordered the population to gather on his way to acclaim him. But at the turn of an alley which had escaped vigilance, the eyes of the prince fell on an astonishing being, such as he had never seen before: frail and bent over a cane, he had white hair, a deeply wrinkled and moves with difficulty. Taken aback, Siddhartha questions his squire: who is this being? Why this astonishing appearance? Is it a unique case? The answers mark a decisive turning point in his life: “Lord, he is an old man. The weight of years weighs on his body which is no longer as alert as before. He is nearing the end of his life. It's all of us. Myself, yourselves, your father King Çuddhodana… we will all one day become old men like this. » Deeply affected, the prince asks to return to the palace.

In the weeks that followed, the same destabilizing pattern repeated itself. Confronted with a patient rejected by everyone for fear of contagion, abandoned in the street, on the ground, Siddhartha again questions his squire. A little later, it is a corpse around which the relatives of the deceased lament. For some texts, it is a funeral procession that accompanies the body of the deceased to the place of his cremation. Harsh discovery of illness, death and suffering who accompany them.

Another life is possible

The fourth meeting is of another nature. Siddhartha finds himself face to face with a man very humbly dressed in yellow — the traditional color of renunciation in India — who begs for his food. But he emanates from him an impressive serenity. And this time, the prince descends from his chariot to question him in person with respect. He thus learns that he has before him a renouncer, who has abandoned his privileged environment after realizing the vanity of the things of the world to embark on a spiritual quest. The parallels are striking between the approach of this renouncing religious, similar to many others who then traveled the roads of India in search of the Truth, and that of the future Buddha.

Even more pensive than after the first three meetings, the prince returns to the palace. An irreversible process started in his mind. He opens up about his trouble with his father, but the latter's attempts to hold him back will have no effect.

Leave to find yourself

Some time later, after an evening of rejoicing in the gynaeceum, Siddhartha wakes up in the middle of the night. He sees his wife asleep, the women in his suite and the pretty dancers slumped, abandoned to sleep. An unflattering comparison between his father's palace and a mass grave comes to his mind and convinces him that the time has come. He calls his faithful squire, has his horse brought to him. It is the Great Departure, which the golden legend of the Buddha has enriched with multiple wonders. The inhabitants of the palace are magically asleep, a cohort of deities, very happy with their decision, form a procession to escort the prince and his mount, which the four protective geniuses of the city carry by the air above the walls to go and deposit them. in a place far enough away that they cannot be reached. There, Siddhartha cuts his hair, gets rid of his precious clothes and finery, entrusts them to his squire whom he enjoins to return to court and inform his father of his decision. The die is cast.

The day Siddhartha compares his father's palace to a mass grave, he realizes that the time has come to leave.

It's a safe bet that these four encounters, decisive in the course of the future Buddha, doubtless did not take place in such a rigorously similar manner as the texts in which they are actually described according to the same narrative scheme present them. But the lesson that can be drawn from the first three, with old age, illness and death in particular, remains: brutal contact with the reality of human experience, unsatisfactory and painful. First glimpse of the impermanence of conditioned phenomena that we all face, but that it is us, it is me, while my father, now 86, is going through trying times, if difficult to accept. It is in this type of circumstance that I perceive the gap which separates the theory of the texts, which I know speak true — we cannot deny that everything is impermanent — and the practice of acceptance and letting go